Key Takeaways

Anyone who has enough work credits paid into Social Security can begin drawing retirement benefits as early as age 62. But is it worth it?

Older adults who aren't drawing Social Security yet may find themselves ineligible to receive the Medicare Savings Program benefit.

Learn how to help clients struggling financially to weigh the pitfalls of drawing early Social Security benefits.

Have you ever had a client come in looking to add a little extra to their monthly budget and discovered something that might help, only to find out there was a major pitfall that could derail them from receiving the benefit? A counselor in Connecticut recently ran into this exact problem when talking with our friend George.

George is 65 and still working, but struggling to make ends meet on his current income. After talking with the counselor at his local aging office, they discovered that George was potentially eligible for a program to pay his Medicare Part B premium—the Medicare Savings Program (MSP). But when he applied, his state Medicaid agency (which administers the program) denied the benefit. The reason? George is not taking his Social Security retirement benefits yet, and thus is not pursuing all sources of income available to him before requesting help from the state.

The Pitfalls of Early Social Security

Anyone who has enough work credits paid into Social Security can begin drawing retirement benefits as early as age 62. However, taking Social Security early reduces the amount of money the individual receives for the rest of their life, while waiting until later than the full retirement age increases the benefit amount.

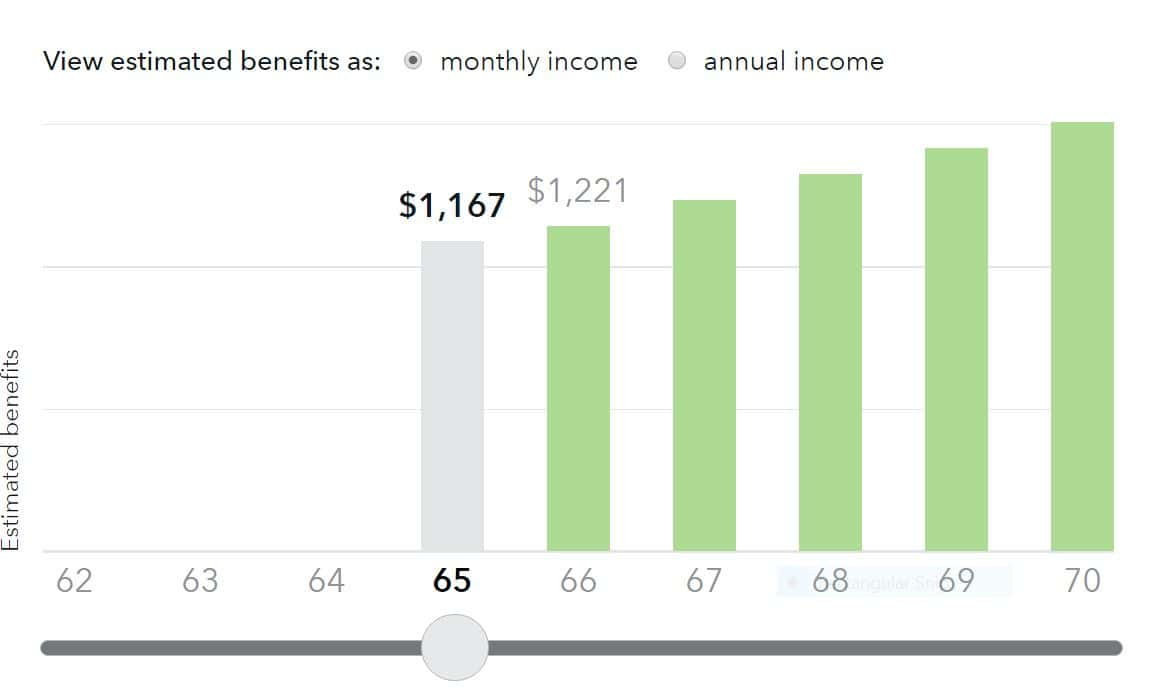

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) has released an online Planning for Retirement tool, which helps consumers calculate how much money they’ll lose or gain depending on the age they first take Social Security retirement benefits. Here’s what it shows for someone like George:

Source: Estimates made using CFPB Planning for Retirement tool

Source: Estimates made using CFPB Planning for Retirement tool

Let’s assume George’s highest ever annual income was $45,000, though he earns less than half that amount now (In Connecticut, a person can qualify for MSP with annual income up to $29K). If George takes Social Security today at age 65, he will receive a monthly benefit of $1,167, or 4% less than what his benefit would be if he waited until his full retirement age of 66.

That difference of $54 each month may not seem like a lot now, but if George lives 20 more years, that’s a loss of nearly $13,000 in total lifetime benefits.

Can Clients Be Forced to Take Early Social Security?

Medicare Savings Programs are administered by state Medicaid agencies, which have some flexibility in setting MSP eligibility requirements. Some states, like Connecticut, eliminate the asset/resource test and/or raise the income threshold to higher than the federal levels. Federal law (42 CFR 435.608) mandates that:

As a condition of elibility, the [Medicaid] agency must require applicants and beneficiaries to take all necessary steps to obtain any annuities, pensions, retirement, and disability benefits to which they are entitled, unless they can show good cause for not doing so.

However, what demonstrates “good cause” is open to interpretation by the state. Forcing a person to take early retirement and thereby endangering their long-term economic security may/may not be considered good cause. Some states may not be clear on the rules. Others, like New York, have issued special guidance stating that Medicaid applicants who are still working and have not reached full retirement age cannot be forced to take early Social Security.

How to Help

If you have clients like George, it’s important to do two things:

- Clarify your state’s Medicaid rules. Find out whether the state has issued any guidance about whether applicants who are pre-retirement can be forced to draw down their Social Security benefits early, and advocate for clarification of the “good cause” clause.

- Examine each client’s case individually. Weigh the financial gains and losses together so that the client can make the decision that is best for him/her over time.

In George’s case, this means reviewing two possible scenarios with him:

- George might decide the value of getting MSP to pay his Part B premium is worth losing an extra $54/month in Social Security.

- He may also consider whether it makes sense to apply for MSP after he reaches his full retirement age and collects Social Security then. George would be responsible for paying his Part B premiums in full until that time, but might weigh the loss worth the eventual lifetime gain of a higher benefit.

It's also important to remember that people with Medicare who do not draw Social Security benefits are not protected by the "hold harmless" provision, meaning they are affected by increases in Part B premiums.

If you have a client like George, look holistically at his income sources, debt, and whether he qualifies for other money-saving benefits to select an option that works best for his situation.